How Peter Sprague Saved the Aston-Martin Company

A venerable brand, Aston-Martin almost went out of business in the early 1970s. If not for businessman and entrepreneur, Peter Sprague, we may have missed 007, James Bond, avoiding international bandits in his Aston Martin.

We thought our audience of manufacturers would enjoy the story of saving Aston-Martin. Many manufacturing companies have experienced good times and bad times, and Aston-Martin was no exception. Timing was right, as the company was about to go out of business, Peter Sprague read the story in the New York Times and decided to visit the manufacturing facility. The rest is history, a very interesting history.

Many manufacturing companies have experienced good times and bad times, and Aston-Martin was no exception. Timing was right, as the company was about to go out of business, Peter Sprague read the story in the New York Times and decided to visit the manufacturing facility. The rest is history, a very interesting history.

To read the abbreviated version of his story, continue below, or click the link to check out the full story on Peter Sprague's website.

SWIFT RUNNING

by Peter Sprague

PROLOGUE

On Monday, December 30, 1974, people all over England went back to work after their Christmas break. In Newport Pagnell, a small town about an hour northwest of London, over 500 men and women went to work at Aston Martin Lagonda, the town’s largest employer. Some were able to walk to work; many had worked there for decades. There was a pattern to their daily lives. This Monday was different—the factory was locked.

There had been no real warning. Things had not gone well for the previous few years; ownership had changed and seemed to have no direction. Company assets appeared to evaporate along with the sports field in back that had been taken away from the local cricket teams and sold to developers. Things had emerged in a darker shade of gray. Now they looked completely black. Everyone milled around the closed building and compared rumors and misinformation.

The name Aston Martin conjures up images of elegance and power. These images are not supported by the factory visage in Newport Pagnell; a hodgepodge of brick additions sprawled inelegantly around “Sunnyside,” the headquarters building, a dilapidated small faux Tudor house of modest pretensions built for Mr. Salmons early in the 19th century.

An announcement was posted on a few doors that told everyone to meet at the cinema in town the next morning. Ironically, the theater was owned by the daughter of one of the Salmons family descendants.

At the meeting, marketing manager Fred Hartley welcomed everyone and introduced Michael Clark. The company was pronounced bankrupt, and Michael was the receiver. The creditors were in control. The terms of redundancy were explained. In most cases, there were no jobs to go back to. The Service Department would stay open, but the factory would remain locked.

Craftsmen had been making wheeled vehicles in Newport Pagnell since 1820. Before Aston Martin there was Tickfords, who made carriages, and then later bespoke automobile bodies, and before Tickfords there was Salmons who made bread wagons and hearses. A few of the men and women at the cinema that day had family who had worked at the same location for four generations. The pubs must have been busy that gloomy Monday evening.

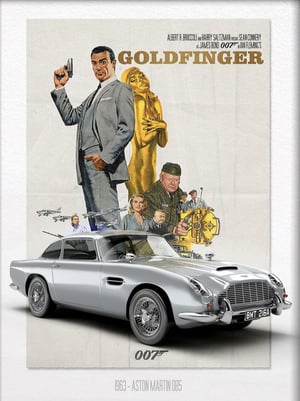

The next day, the press announced to the world that Aston Martin was bankrupt and closed. There were few places so obscure that the news was not heard and repeated. James Bond’s car had been finally destroyed by the villains of commerce. Ten thousand Aston Martin owners wondered about the future of their cars. People who had owned Astons in the past were given to reminiscing. People who had dreamed of owning a new Aston in the future knew that there would be no new Astons. Another famous automobile company had died.

That evening, Walter Cronkite delivered a eulogy for Aston Martin on the CBS Evening News wearing a black tie. It has been reported that he rarely did this for man or beast.

I am sure that there was much in the news that day to get upset about. There usually is. But Aston’s demise really bothered me.

In 1962 I had bought a used 1960 DB4. The ads said it could go from 0 to 100 and back to 0 in less than 26 seconds. It could and did. It became my wife Tjasa’s car. At the time, I had an Alfa Romeo Spyder that eventually wore out. When we moved to New York in 1962 with our son Carl, we sold the Alfa, and the Aston was our only transportation. Son Steven soon arrived, and we would pile the kids in the back, on a foam-covered plywood panel, where they rattled around in pre-child-seat bliss. Finally, sons Kevin and Michael arrived, and we bought a larger car. But the Aston remained in the family. We still had the car in 1974.

I had been to the factory in the early 60s with my future brother-in-law, and again in the late 60s when we shipped the DB4 to Newport Pagnell to acquire a sunroof. I had wanted to take a factory tour but was not important enough to get one. I still had a sense of the people and the craftsmanship from my visits, a feeling that anyone who visited “the Works” in those days must have felt. It was far from Detroit mass production; far from the microelectronics that I was involved with—it was a special place that brought to life prewar photographs of a different world.

I emerged from the tub frustrated by Aston’s demise, and announced the news to my family in the kitchen with the comment, “Why did that have to happen?” Off and on over the next two days, we kept returning to the question of why Aston had to go out of business. Finally, Tjasa brought my complaining into focus: “Why don’t you do something about it?” I had been up to my neck in hot water when I read the news. I did not realize that this was just the beginning.

I turned to a young friend who was staying with us, Morris Hollowell, and said that if he could get me the name and telephone number of the managing director in England, I would call him up and possibly go over to England after the weekend. Morris tracked down Rex Woodgate, who represented Aston in the U.S. Rex volunteered the name of Charles Warden, along with his phone number. I called Charles and briefly introduced myself and set up a meeting at the factory on Monday morning.

AMERICAN MILLIONAIRE TO THE RESCUE

I was the perfect person to get involved in Aston Martin. I was 35 years old. I knew nothing about any aspect of the car business. I had never been inside the factory or met any Aston luminaries other than Rex Woodgate. I was not as impressed as I should have been that the British economy was in terrible shape, The Financial Times stock index was at 176—today it is over 4,000. There were even discussions of a possible intervention by the World Bank. Things were grim, but I was cheerful—I truly did not understand the situation.

On the positive side, I had had some experience with startups and troubled companies. At the ripe age of 26 I became chairman of National Semiconductor when the company was coming out of receivership. By 1970, National was on the NYSE. I had learned entrepreneurship by starting a chicken farm in Iran with Iranian, Lebanese, and American partners. I had also become involved in several enterprises along the way, both failures and successes. But no car companies, large or small.

My education consisted of political science at Yale and MIT and economics at Columbia. My first job at age 17 was as a photographer for The Berkshire Evening Eagle in Pittsfield, Mass. I continued as a photographer with United Press International (UPI) in Russia in 1959 covering the “kitchen debates” of Khrushchev and Nixon. Tjasa and I visited Outer Mongolia for UPI in 1960. We were the third and fourth Americans to make the trip after WW II.

In 1970, I lost a Congressional race against Ed Koch in NY. A less-than-perfect background for the upcoming events at Aston. I did have a lot of energy. I did not have enough money to buy a car company.

It is possible that I would not have become seriously involved with Aston if I had not been ensnared by the British press. When I arrived late in the morning of January 6, 1975 in Newport Pagnell, I was astonished to find 30 to 40 reporters and photographers elbowing each other in an enthusiastic scrum around the V8 the company had sent to pick me up. One question that was asked was, “Who are you?” I announced that I wasn’t anybody. That really raised the interest level. Charles Warden desperately wanted to keep alive the possibility that Aston could be saved. It seems that I was the first to show interest. He had called members of the press and announced that “an American” was coming over to save the company. I was a thin straw to grasp.

It appears, in retrospect, that nothing of any importance occurred anywhere in England, or perhaps even in the world at large on Monday, January 6, 1975. There being no other news, my visit to Aston made the front page of a wide variety of newspapers including The Evening News, who trumpeted a page-one banner headline, “Millionaire to the Rescue.” The article began, “A millionaire without a name toured the Aston Martin factory this afternoon and said that he hoped to save the company. The man, an American aged about 35, bearded and wearing spectacles said, ‘I cannot reveal my identity at this time.’” I did not actually say that, but that’s the quote.

There was a dramatic picture on the front page of me clutching a pipe, with my tie in the wind, looking rumpled. If they didn’t know who I was, it is curious to know how they concluded that I must have had a million of something. They did not specify the currency.

The following day, the press knew my name. I was, in fact, not anyone in particular. I decided I could not leave England after having raised everyone’s expectations without taking a thorough look. I felt then, as I do now, that you do not play with people’s emotions lightly. Aston Martin Lagonda meant a great deal to a wide variety of people. From owners to dreamers, from craftsman at the works to suppliers, from small boys to their older equivalents, Aston was important to a wide cross-section of people. As a result, it became important to me.

Charles Warden took me for a walk through the factory. It was an experience that I still vividly remember. A week before, everything had stopped without warning. We started with the raw material, racks of sheet metal and leather and parts, walked down the production line and I imagined the process of a car coming to life. Except there was no life, only an eerie quiet with a background aroma of leather and oiled metal. I wanted to see it come alive again. I did not know how difficult it would be or how long it would take, but I became emotionally hooked.

I determined that I would put in a month to better understand what had gone wrong and what could be done. Facts were hard to come by. Aston Martin Lagonda had been acquired by Company Developments Ltd. William Willson, the principal of Company Developments, had installed a receiver (Michael Clark). They did not seem too happy about my arrival and inquiries. Most of my time in Newport Pagnell was spent in an uncomfortable wooden chair in a small office in the unprepossessing headquarters building in front of the factory. The receivers’ frugality on behalf of the creditors included not providing heat. It was January and damply chilly.

Aston’s employees were at least able to liberate their tools. Newport Pagnell is a tight community. Everyone knew everyone, and most of Aston’s former employees lived in town. The night watchmen turned a blind eye, and tools and tea mugs migrated to their rightful owners. Jack Hilliam, one of the lead panel beaters, rescued his hand crafted “flatters, chasers, flippers, tuckers, and shrinker fitters” among his other tools.

Several Aston craftsmen found jobs at Rolls Royce in Willesden, North London that involved a long bus ride on buses that Rolls Royce sent daily to Newport Pagnell. Jack Hilliam recalls, “We were all in a state of shock and we were really down working at Rolls Royce. Their panel beaters had been on strike for a long time, but we AML people were treated like Gods. I would finish our weeks’ work by Wednesday—I couldn’t work any slower!”

William Willson showed up occasionally, wearing a yellow windcheater and orange socks, or perhaps it was the other way around. I later learned that in the dying days of Aston, Wilson had spent a week or two in Japan enjoying the £1000-a-day Presidential suite at the Okura with a butler and limousine patiently waiting around the clock. The subsequent bill was sent to the Japanese importer and contributed to his later bankruptcy. Photos of Willson enjoying the nightlife of Tokyo somehow had found their way to the factory floor a few days before its closing. That had not inspired the work force. If he had been a more impressive executive, I might have been discouraged.

There were obviously a lot of assets: 110,000 square feet of manufacturing, 14 acres of land, and a new service center that had achieved a profit of £250,000 a year. Over a million and half pounds sterling of parts, £760,000 of work in progress, and 60 completed or nearly completed cars at the factory or in the U.S.

I went looking for partners. Almost every day some new consortium or individual would come forward, usually through a press release, with a stated interest in doing something. I was open to all possibilities, including bowing out gracefully, if I could find someone determined to go ahead on their own. I would not have been unhappy if someone else brought the factory to life. I could go home and buy a car from the new owners.

THE PROBLEM

The basic underlying problem was that it appeared Aston Martin Lagonda had never in its history made a profit. One of my favorite David Brown stories, possibly apocryphal, was that when approached at a cocktail party by a gentleman who asked if Brown could arrange for him to buy a car directly from the factory, at factory cost, the reply was, “Certainly—that will be two thousand pounds over retail.” Much later on, Alan Curtis and I often used the same response in similar circumstances. In addition, I did not have a team with whom I could develop a plan. The previous management was scattered to the winds. Aston employees were on the dole looking for work, the panel beaters were temporarily at Rolls Royce enjoying a two-hour, round-trip bus ride from Newport Pagnell. I would occasionally walk through the cold and empty buildings and these solitary walks still inspired me to keep going.

GETTING ASTON MARTIN BACK ON TRACK

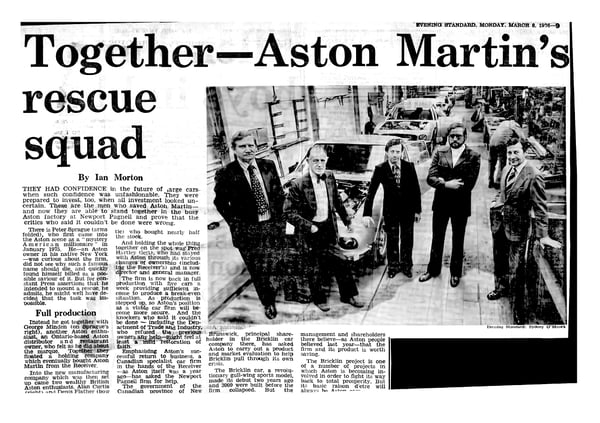

It was difficult to answer the question: “If others have failed, why do you believe you can succeed?” I could not find a convincing reason why it could not be done. I needed enthusiastic support. I found it in the person of George Minden. George was the Aston distributor for Canada. He was a complete and knowledgeable enthusiast of Astons, Bentleys, etc. He had lived in Toronto but had recently moved to England with his wife and two young daughters.

George had a specific problem. A few weeks before Aston went into receivership, he had purchased six new Aston V8s from the factory. He was given no warning of the impending financial problems. He knew that he would have major problems selling the cars if the company was permanently going out of business. He called his own press conference in Canada to announce that he was interested in putting a consortium together to save the company. His news conference received wide coverage. I called him up to tell him that I was glad that he was going to save the company and offered to support his efforts. George was surprised by the interest that his press conference had stirred up. He was also surprised by my call. He did not intend to save the company on his own. We met in London at the Dorchester and agreed to work together.

I flew up to Toronto from NY and met with the head of George’s operations, John Cox, a cockney former welterweight boxer who added his enthusiasm and convinced me that we could do a better job marketing the cars.

We stayed in regular touch after our first meeting. I had someone whom I could talk to who did not feel that my goals were completely quixotic. Without him, I might have simply fallen off my white horse from frustration and exhaustion. George said that he would invest working capital if we were able to acquire the assets from the receiver. I had well over 100 meetings during the first six months of 1975 in pursuit of cash or partners in an effort to restart the company.

I met with investment bankers in NY and London. With dozens of individuals and groups, from Jarvis Astaire the gambling impresario, to Aston Martin Owners Club enthusiasts, and many who seemed only to be interested in tagging along for publicity that involvement in Aston always seemed to engender.

I was searching for “yes.” I rarely got a “no,” people usually just drifted away, though after two meetings with Jacob Rothschild, he was polite enough to offer a proper “no.”

The major problem that I faced was the fact that William Willson, Company Developments, and their receiver refused to set a price for the assets, avoided negotiations, and seemed to have little interest in reaching a conclusion. Willson had stated on numerous occasions that his goal was to help bring the company back to life. He eventually lived up to that commitment. But it took a while.

My own finances were improving. My major asset, National Semiconductor stock, rose significantly during the spring of 1975. I went to National’s bankers, The Bank of America, where I met a courageous banker who agreed to loan me £600,000 against the 60 mostly completed cars.

In late May I decided that I would try to purchase the assets on my own, and then sort out the situation afterwards.

I managed to get myself invited to William Willson’s home in the country for a weekend. I had heard that he was planning to sell the company to an American company called Robert Carl Associates. My assistant, Carla, managed to track them down to a Detroit-based industrial liquidator who had created Robert Carl Associates for the occasion. I called a few of the journalists I had met in the springtime, gave them Willson’s home telephone number, and suggested they call during the weekend and inquire why he was selling the company to a liquidating firm after his promises to help put Aston back in business. As part of my diplomacy, I let Mr. Willson beat me at ping-pong. At least that is the way I like to remember it. By the end of the weekend, we had agreed on a price he would support; he even volunteered to help with the financing by providing a short-term loan.

There was £300,000 in the receivers account, I had £600,000 committed by the Bank of America, and I agreed to provide an additional £170,000—for a total of £1,070,000. That was my offer, and after weeks of discussion, they accepted it. There were no other bidders and no one else had come forward during the previous six months. Effectively, I was buying all the assets of Aston Martin without liabilities for £170,000 cash. I could have kept the name and the service business and sold off the assets for a few million pounds.

Because we needed a company with which to buy the assets, Slaughter and May produced TruShelfCo #23. We changed the name to Aston Martin Lagonda (1975) LTD after we acquired the assets. Five years later, we were allowed to drop the (1975). I needed an English shareholder for some of the transactions. A trustworthy friend of long standing, Jan Dauman, became that shareholder and I believe for a very brief time became the owner of Aston Martin, or at least a part of it.

produced TruShelfCo #23. We changed the name to Aston Martin Lagonda (1975) LTD after we acquired the assets. Five years later, we were allowed to drop the (1975). I needed an English shareholder for some of the transactions. A trustworthy friend of long standing, Jan Dauman, became that shareholder and I believe for a very brief time became the owner of Aston Martin, or at least a part of it.

I arrived for the closing in Birmingham on a rainy Friday afternoon in a parking lot outside an office block in Sollihull. For reasons I never understood, we could not meet indoors where some enterprise of William Willson’s had an office.

William Willson, Michael Clark, my lawyer, his assistant, and I stood in the rain exchanging documents. Suddenly, my attorney blurted out. “We can’t have a closing.” It seems that we could not have a closing unless the check was from a British Clearing Bank. A cashier’s check on the Bank of America was not good enough. What would happen if they went broke over the weekend and the check did not clear on Monday? I suggested that we close “subject” to the check clearing on Monday. My very thorough attorney then spent the next 20 minutes explaining that a closing “subject” to anything was not a closing. I enjoyed the lecture on the finer points of British jurisprudence, as my spirits became as damp as my suit.

I agreed with everyone in sight, apologized for the Bank of America, admitted that I was disastrously ignorant, and eventually we sort of “closed.” A little groveling sometimes goes a long way. The Bank of America did not go bust over the weekend, World War III did not break out, and I officially owned the company on Monday.

As far as I was concerned, I owned it on Friday. The sensation was strange. I was glad the six months were over. I had no real plan for the next six months. I felt more empty than elated. The following morning The Daily Mail ran a wonderful cartoon showing a small boy praying beside his bed with his mother standing behind him. The caption read, “You needn’t include Aston Martin tonight dear, it’s being saved.” What was I going to do to live up to the expectations of the small boys of England and beyond?

I felt thoroughly daunted.

I still needed a fully active partner at Aston. George Minden has one foot out the door into retirement. I needed someone who would be fully committed. Of all the people who I had talked with that spring, one individual stood out. I called Alan Curtis. His teenage son, who was an Aston fanatic, answered the phone, and in a reverential tone said to his father, “Peter Sprague is on the phone.” Alan later said that he agreed to join in the effort because he couldn’t disappoint his son. Alan had been in construction and loved airplanes. He flew the only British Bulldog aerobatic airplane in private hands. He had earlier insisted that he had no interest in cars and would not invest.

He was the right man for the job. I asked him to come and visit the factory before he turned me down again. He agreed. The evening before the visit, we had dinner at the Dorchester. By good fortune I had ordered a Chateau Becheville Bordeaux, which turned out to be his favorite wine. I ordered my lamb rare; Alan had his well done. I reached over the table to sample a burnt specimen. This isn’t done in England. Alan later admitted that he decided to become my partner because it was unlikely that anyone else would.

The next day we went to Newport Pagnell. Once more, I walked through the empty factory, which this time I owned. The gloomy dead factory once again worked its magic. Alan signed on and agreed to invest and join the Board. The rest of this story involves Alan at least as much as it involves me. I had a partner and a new friend. I needed both.

RESTARTING THE COMPANY

Slowly we began to restart the company. Fred Hartley led the effort. We had an auction of the exotic bits and pieces that were lying around. Members of the Aston Martin Owners club showed up and bought £17,000 worth of stuff. We used the money to buy drafting tables and restart the engineering team. We began to complete the last few cars on the line. They were finished in the Service Department. Slowly, laid-off members of the factory team began to rejoin the company.

As we started to put the company back together, we put more and more trust in the workforce—the men and women who actually built the cars on the line. Former “managers” with British public-school educations and unclear job descriptions were simply not rehired. Our extraordinary production manager, David Flynt, went to the workforce and stated the obvious. If we keep operating as we had in the past, we will go out of business again. We had to make changes and become more efficient.

One of my favorite examples of the inefficiency of having a labor force that does not communicate was the case of the “excess bracket.” We found that one craftsman with great care was welding a bracket on to the frame. An equally fine craftsman was removing the same bracket with equal care three stages down the production line, about 40 feet away. They had tea together every day. No one knew what the bracket had ever been used for. In the old way of doing things, there was no motivation to change this procedure, because eventually, it might lead to a loss of employment for one or both of the two people involved.

David Flynt changed this and the fundamental mindset behind it. In the first six months, there were over 2,300 engineering change orders, most of them initiated by the workforce. Years later, at an event at Silverstone race circuit organized by Alan Curtis where all the employees and their families had a picnic and everyone got to drive in an Aston (most for the first time), one of the employees was interviewed by ITV television. When asked what he thought, he stated, “It used to be them and us—now it’s us.” The change began when the factory restarted. The company picnic was on a Wednesday. Alan asked everyone if they could make the same number of cars that week in four days that normally took five days. They did, and it was a great success.

Around 1978 there was a major strike at Lucas, our major source of electrical and lighting parts. Lucas was often unkindly referred to as the “Prince of Darkness.” We had few parts on hand, and if we could not continue to be supplied, we would have had to cease production in a few weeks. Alan drove up to Lucas in a new convertible V8, with the top down. When he arrived at the door, there were 100 or so pickets with the usual paraphernalia of corporate strife. Alan introduced himself and explained what he was there for: Aston needed two-week supply of parts. They opened the gates; then Alan filled the boot and back seat with what we needed and drove off. The parting words of the gang at the gate were, “See you back in a fortnight, Guv’nor.” We survived.

In general, I always had the feeling that almost everyone we dealt with wanted to see us continue to survive. There were a lot of Aston enthusiasts who could not afford to buy a car, but had a sense of ownership because they were personally involved.

Over the next few years, it became crystal clear that the greatest asset at Aston never made the receiver’s balance sheet. The men and women were extraordinary—driven away from production lines and towards craftsmanship by their intelligence and curiosity. I would have guessed that their IQs would have gotten most of the employees into a good university in a more democratic world.

We expanded our Board of Directors. In addition to Alan Curtis and George Minden and myself, we were joined by Dennis Flather. Dennis had made his industrial fortune in the steel business in Sheffield. We had been getting a lot of small donations from children who would send a few pence or occasionally a pound or two. Dennis sent a check for £50,000, with the note that we would probably need it. Neither Alan nor I had ever met Dennis. We called him up and arranged to meet him at the factory and have lunch.

THE FUTURE

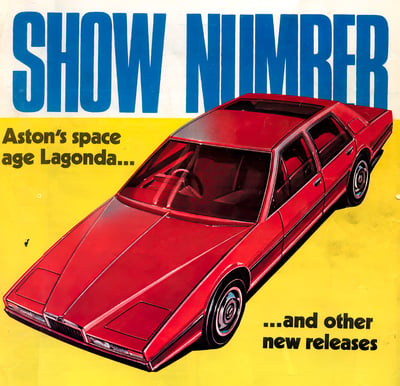

A few weeks after the 1975 Earl’s Court Motor show, we began to discuss the future. As a team, we had only begun working together for three or four months. We knew that we needed a new model. One obvious choice was to put a new body on the V8 chassis. The existing body design had been around in one form or another since the introduction of the DBS in 1967—and was getting tired.

Moreover, the V8 chassis had too many separate parts and was very expensive to build. Michael Loasby had just rejoined the company as head of engineering; he believed he could develop a much-improved chassis that would be less costly to produce.

We then debated whether we should create a brand-new coupe to replace the V8, or revive the Lagonda marque around a four-door car. A major concern was that if anyone learned that we were building a new two-door to replace the V8, the market would stop buying the existing model while they waited for the new one. In the interim we could go out of business. I remembered the fate of the Osborne computer company, which had just failed, en route to the future. They had announced a new model months before they could produce it. Everyone waited for the new and ignored the old. The company ran out of sales and cash.

Later that fall, we had another meeting for a presentation by William Towns. He produced a drawing of a spectacularly radical four-door design. We decided to go for it. I believe that the decision was made in a day. The four company directors all felt that we wanted to own the car in William’s drawings. We would never be able to drive it if we didn’t build it. Thus, the Lagonda was conceived. We had a little over nine months until the next motor show, and we had 11 exceptional engineers. We decided to keep the whole project a secret.

I have been asked many times whether we had done any market research, was there a detailed budget, and what gave us the confidence that we could do it? Basically, we looked at William Towns’ extraordinary drawings, and we asked Mike Loasby if he and his team could build it. They said, “Yes.” We had confidence in the team.

As the Lagonda began to take form, I added my own special contribution—related to my background in microelectronics. The car looked amazingly modern, why not add an all-electronic, computer-based information and control system, and really join the 20th Century? It was an excellent idea—but ultimately about 15 to 20 years ahead of its time.

Under William Willson, the company had not kept up with the safety and pollution requirements of the U.S. and Japan. We needed those markets to survive, and began to re-qualify. Despite our production of less than 250 cars a year, we had to meet the same requirements in England and the common market countries—Switzerland, the U.S. and Japan—as Toyota and General Motors. We had only a one-man team led by David Orchard to accomplish the nearly impossible. General Motors probably had more people working on these issues than Aston had employees.

We were assured by engineering that meeting the U.S. requirements would be a piece of cake. We had six months before time and financing ran out. We failed the six-hour endurance drive around an oval track in Ann Arbor, Michigan twice. With two weeks left, the piece of cake was getting stale.

This became a typical Aston story. The night after the second failure, the two Aston engineers who were with the car in Ann Arbor were easing their frustration with a few beers. Next to them at the bar was a 19-year-old driver who coincidentally had been driving the test Aston that day. He worked for the EPA.

The engineers introduced themselves. The driver began to express his opinion of Aston Martin Lagonda in forceful terms: “You cheap bastards, if you want me to drive reliably and steadily around the same boring oval for six hours the least you can do is put in a music system.” We had shipped a stripped-down car without a radio. The engineers called me in Lenox. They were out of money. I wired cash through Western Union. The engineers bought and installed an 8-track cartridge player. The driver loaded his own cartridges. Three days later we passed the test. We sold the cars, paid the loan, and did not go directly to jail. We had dodged another bullet and our luck had held.

BACK IN PRODUCTION

Back at the factory, we were producing four to five cars a week and paying our bills with difficulty. We maintained the myth that we were completely sold out for a year. Otherwise, we feared that no would have felt the need to buy a car. We needed the world market

We finally re-qualified to sell our cars in Japan. As usual, this wasn’t easy. The bureaucratic “official representative” of all foreign carmakers in Japan was chosen, not by the car importers, but by the Japanese government.

One of the tests required was that we place a four-inch board covered by a nylon stocking two inches from the end of the exhaust pipe while the engine ticked over at 1500 rpm—for two minutes. If the stocking burst into flame or melted, we would be required to redesign the exhaust system. Presumably this was to protect Japanese women from spontaneous combustion if they found themselves with a stocking-clad, wooden leg lingering behind an Aston. But we eventually passed. At least we didn’t have to crash-test the car. All that hand-hammered metal crunching a concrete block! That was a requirement in both the U.S. and Britain.

Aston had previously sent over an English mechanic, Dennis Nursey, to Tokyo. He reported that there was a James Bond tape in every car that came in for maintenance. Despite the fact that the Japanese drive on the same side of the road as the English, they ordered left hand steering wheels to emphasize the foreign source of the cars. They needed the panache of James Bond to put the extra four feet of metal into the onrushing traffic to see if they could pass. On the other hand, most Tokyo traffic didn’t allow the driver to get out of first gear.

In 1974-75, Dennis worked with Eastern Motors, the Japanese Aston distributor. He heard about the collapse of Aston on Japanese radio. No one had informed him that the company he worked for was no longer in business. He returned to Newport Pagnell, where it felt like a ghost town.

In late 1975 Dennis rejoined as a service engineer. Chubuyashima took over the distribution from Eastern Motors and ordered 40 cars a year for 1976 and 1977. Aston had been selling eight to 12 cars a year in Japan. It was a brave order and very helpful. They still had a large inventory in 1978.

We had a worldwide network of dealers. Alan kept them all involved and interested. They kept us alive.

In the States, Morris Hallowell took on the responsibility for distribution, and we opened a retail store in Greenwich, Connecticut. Rex Woodgate eventually returned to Newport Pagnell where his great technical skills and knowledge were devoted to special projects.

The Lagonda was beginning to take extraordinary shape. By now we had 17 engineers, most of whom were working on the project. The car was not designed by a committee—William Towns was responsible for the entire design, inside and out. The result was a striking piece of mobile sculpture. The Lagonda looks as modern today as it did 25 years ago.

The nine months our team had to get the car ready for the 1976 Earl’s Court Motor Show seemed enough time, considering that it was about the same length of time that it took for other designers and craftsman to build the first Spitfire during WW II. We came very close. There was a great deal of improvising. The pop-up radio popped up with the aid of a mousetrap mechanism that had been found at the last moment, and the lid of the box between the seats used a hinge that was taken off a toolbox that was conveniently nearby.

Two weeks before the Motor Show, we had a special press preview. Our secrecy was such that there was not even a rumor that we were doing anything radically new. Alan arranged for a lunch at the Bell Inn in Aston Clinton, near the famous hill climb that gave Aston Martin its name. Lionel Martin had won the hillclimb there with his car, and it became known as the Aston Martin. There were about 120 people at the lunch. Geoff Courtney, our creative PR genius, had rounded up the British motoring press, who, while doubtful that we would produce any real news, were confident that they would have a very good meal while enjoying each other’s company. Geoff also rounded up members of the Lagonda Club who brought with them a beautiful selection of mostly prewar Lagondas. All the Aston directors were there along with many of the men and women from the Works who had been present at the creation. My wife and children flew over for the occasion. I was thrilled, proud, and excited.

The curtain was pulled back, and you could hear the intake of breath. Nobody expected what the team had accomplished. Resplendent in silver, the car glistened like a jewel under the lights. We had kept the secret—and it had been worth keeping.

As the show was a “preview,” we tried to embargo the news until the morning of the Motor Show. We admitted to the press that the car was not a “runner.” It lacked a transmission, but the displays and most of the rest worked. The press agreed to restrain themselves until the Motor Show opened.

The BBC broke the embargo on the evening before the Motor Show. We expected they would broadcast the film they had taken on the morning of the show. Instead, they showed the car traveling gently through a section of seductive English countryside. The rest of the press was furious. Not only had we not enforced the embargo, but we had lied to them about the car. It obviously ran, despite our assertion that it didn’t. We assured them that despite the evidence to the contrary, the car did not run.

The truth was that we had taken the car out on a low loader (flatbed trailer) to the top of a pristine hill somewhere near the Works. The BBC placed some construction blocks into the boot to compensate for the weight of the missing transmission and had then filmed the car as it rolled gently downhill through the countryside, complete with driver. It looked great on the evening television, even if they had scooped the rest of the press by a few hours. We apologized profusely to all and sundry.

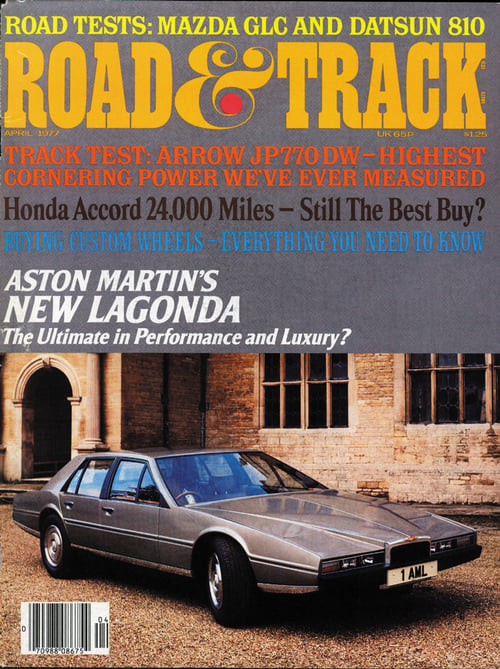

Motor Show day finally dawned. The Lagonda was on a platform under spotlights. It deserved its limelight. I believe it is fair to say that we stole the show. Prime Minister James Callaghan sat in it and Colin Chapman of Lotus brought over his chief engineer Mike Kimberley to have a look—and asked him why Lotus couldn’t have the same exciting instrumentation.

deserved its limelight. I believe it is fair to say that we stole the show. Prime Minister James Callaghan sat in it and Colin Chapman of Lotus brought over his chief engineer Mike Kimberley to have a look—and asked him why Lotus couldn’t have the same exciting instrumentation.

The high moment of the day came when a smiling American came by and complimented the car. A BBC reporter recognized him and asked if he would comment for attribution. “It is a magnificent achievement; we tried to make the new Cadillac shear, but they made it shearer,” said William Mitchell, the legendary head of General Motors Design. His generous comments resonated all over England.

The press photographed it, TV filmed it, and everybody wrote about it. The notices were sensational. It looked like the Aston show might enjoy a longer run than expected.

BACK IN BUSINESS

It may not have been reflected in our balance sheet, but as far as the public was concerned, Aston was back in business. We were back on the front pages all over the world.

The team at Aston had risen to the occasion and deserved the applause.

More importantly, we received 76 orders at the 1976 Motor Show, mostly for Lagondas. Nick Mee and Colin Thew remember driving from embassy to embassy collecting deposit checks.

But, we still had much work to do. The car still wasn’t a runner. We had a backlog of customers from around the world and a non-working prototype. We needed to start making Lagondas.

In 1977, when we were ready to deliver the first Lagonda, the delivery was not going to be a secret. We told the press that we had a mystery customer and would release the first car at a midday event at Woburn Abbey. We had been very optimistic about our completion schedule. It is easier to build a prototype than to build production automobiles on a manufacturing line.

The night before the delivery, I visited the factory with Lord Tavistock at about 3 a.m. There were 14 people still working on the car. Six or seven of them had their hands in the engine compartment. I commented that it looked like they were taking an appendix out. They replied the situation was worse than that—they were trying to put an appendix back in.

It turns out that National Semiconductor’s IMP-16 computer board had developed a glitch. It didn’t work, and the car would not run. Back then, we were not surrounded by teenage computer wizards.

As the day dawned, it became clear that we were in trouble. The Lagonda was supposed to drive to Woburn Abbey at 11 a.m. We had invited the press. All the TV channels were planning to send crews. The food and drinks in the Sculpture Gallery were already being laid out. People were on their way. Expectations were high. The car was low. We seriously considered canceling the event, but by then that was impossible.

Plan B was to hope for divine intervention before 11 a.m. As such, we needed Plan C, which was to send the car to Woburn on a low loader again and hope that no one would notice.

So the car was towed to Woburn Abbey, which has a magnificent mile-long driveway to the front of the house. The back entrance wouldn’t work, either. It is hard to smuggle anything as conspicuous as a Lagonda. When the car arrived, the press was already there. Our clandestine arrival did not fool anyone. To describe the situation as embarrassing would be to understate the obvious. Alan Curtis looked at me and decided that this would be my turn as co-chairman to “Meet the Press.” There were more than 100 people in attendance and the cameras were running.

Our mystery purchaser was Lady Tavistock, who had arranged with Diner’s Club to buy the £25,000 car on her credit card and then give the Lagonda to Lord Tavistock in honor of their 25th wedding anniversary.

I stated the obvious. “We goofed,” or, more specifically, “I goofed.” I held up the malfunctioning computer circuit board by one fiberboard corner and explained that the computer had packed it in. It had been my bright idea in the first place; the engineers and the factory were innocent. Everything about the car was magnificent with the slight problem that it did not run. It was not the fault of the Aston workforce. It would run the following day.

Late that afternoon, Lord Tavistock drove one of his functioning cars to the factory to thank the workforce. He apologized to the Lagonda team for putting them under such pressure. It was a kind and thoughtful thing to do. One witness remembers that there were tears in the eyes of some of the men.

The press were remarkably gentle. They were willing to give us another chance. As usual, no one wanted to see Aston fail.

In a strange way, the botched introduction worked in our favor. Everybody was pleased to see the car running, and the reaction was enthusiasm and occasional applause. Robin commented that when he drove his Bentley, he tended to stay away from the curb in parts of London because he could feel a kind of class hostility. With the Lagonda, he drove close to the curb so people could enjoy seeing the car. We were not just an expensive car for wealthy aristocrats and rock stars. We had a broader audience of people who were glad to see that a small British company could produce a beautiful car that made people smile.

Kingsley Riding-Felce, who then worked in the Works service department, remembers driving PUR 106R, a gray Lagonda, down to London and having pedestrians applaud. On one occasion, all the passengers on a bus moved to one side for a better look and it almost tilted the bus into an accident. There were thumbs up all around.

One of the principal reasons that we had committed to the Lagonda project was that the engineering force had cautioned us that it would be very difficult to turn the V8 coupe into a convertible. Our dealer in Beverly Hills, Chick Vandergriff, had assured us that he could sell all the convertibles we could build, provided the top was automatic and worked easily.

Alan Curtis informally discussed the possibility of a convertible with Harold Beach, the legendary Aston engineer, who was helping with a number of special projects. Harold saw no reason why a convertible would not be possible and introduced Alan to George Mosely, who had designed the Bentley convertible mechanism. For £5000 and £150 royalty per car, George gave us a design, including structural reinforcement of the chassis. The structural parts of the top mechanism were designed to be made in wood, an excellent choice for limited quantity production, both stable and rust free. Harold provided engineering support.

Alan met with the workforce and gave them a challenge. Build one car clandestinely on the production line following the new design. Keep the car covered when it was not being worked on. When completed, we would surprise the engineering group. The design engineers were in a small building across the road from the factory, about 100 feet away.

As usual, the factory team met the challenge. Over a two-month period, they kept the secret and completed the convertible prototype. I happened to be in England at the time. We rolled the car out of the factory. The workforce came out to watch. Alan jumped in the driver’s seat, and we drove across the street. Alan leaned on the horn. The engineering group came out to check on the commotion. The latches were released, a button was pushed, and the top went down. Even better, it also went back up with the push of a button. The “Volante” was re-born and went on to be a great success. The workforce had done it again.

We knew that we needed new machinery. It has been commented that one of the unfortunate results of WW II was that Japan and Germany had their industries destroyed and then subsequently rebuilt with new equipment. England carried on with what they had. Aston was building advanced cars with prewar machines that had been used to build the great cars of the 20s and 30s, from Bentleys to Bugattis. It was wonderfully romantic, but very inefficient. Worn machinery cannot maintain the tolerances that were necessary for fabrication and were time consuming to use. Sometimes our “stately factory” seemed more appropriate to museum tours than modern automotive production.

We simply did not have the capital resources to acquire modern numerically controlled machinery. So we too carried on with what we had. It was much better than the alternative of not carrying on at all.

One of our most consistent supporters through thick and thin was Prince Charles. He drove a DB6 drophead and we took pride in the fact that, despite the bankruptcy, we never lost his “three feathers” personal endorsement. Prince Charles once came for a tour of the factory. He arrived at around 10 a.m., piloting himself in a military helicopter.

The day before I had given three different sets of friends and customers a tour of the factory. I began to feel more like a tour guide than a chairman. On the third tour, I met a man working a drill press who I had not talked with before. I rather sheepishly said that I was practicing for the Prince Charles visit. He remarked, “It’s got to give you a lot of pleasure, sir. You worked hard enough for it.” Considering how hard the men and women in the factory worked, I was very much moved by his comment. I wouldn’t mind that quote ending up on my gravestone.

Prince Charles spent about two hours in the factory. I was very impressed by his interest, curiosity, and knowledge. He had something different to say to almost every person he met. I have watched numerous American politicians move through a room with the same, “Glad to meetcha,” for everyone.

Life has taken many twists and turns since that day for all of us, but on that day, he was truly a Prince.

Fortunately, the company directors were not Aston Martin’s only customers. We sold about 200 to 250 cars a year. Despite the macho image, about 20 to 30 percent of our customers were women. Oddly enough, very few people took advantage of our ability to make bespoke cars to their precise specifications. When customers wanted an Aston, they wanted it as quickly as possible. If they walked into Sloane Street, Tony Nugent could easily convince them that while the green car they had in mind was a lovely idea, why not buy the red one that they could drive away today, as there had been a sudden change in circumstances and despite our usual backlog, the car had suddenly become available—a circumstance that might not last until that evening. In addition, there might be a price increase on the near horizon …

To gain customers, we needed to remain in the public eye. We couldn’t afford to advertise, but we needed all the publicity we could get. The major car magazines helped enormously. We provided the cover art and the centerfolds that helped sell them. Ford, BMW, Mercedes, and General Motors provided the advertising. The Lagonda was tailor-made for selling magazines. It provided the drama; the latest Ford Escort did not provide the same excitement. I broke our “no advertising” rule once with a full page, $50,000 ad in The Wall Street Journal. It stated, “147 Proud Englishmen Could Build a Better Car with Their Bare Hands than the Most Advanced Assembly Line in the World.” The ad generated exactly two inquiries and no sales. That was the beginning and the end of our advertising campaign. Fortunately, Alan and Victor were both extremely adept at feeding the press machine.

In retrospect, it is clear to me that the Lagonda was a crucial component for the company’s survival. Arnold Davey has tracked down all the Lagondas built since the first launch of the marque in a 500-page magnum opus. His wife Wendy typed the entire book on a manual typewriter. According to Arnold, there were 633 V8 Lagondas built.

Of these, 164 were shipped to UK customers, 160 were shipped to the Gulf States, 150 to the U.S., 89 to Europe, and 30 to the Far East. In the early 80s, they represented the majority of the cars produced at Newport Pagnell. Customers in Zimbabwe, Venezuela, Taiwan, Sweden, Morocco, Jordan, Iraq, Haiti, Gabon, Congo, and Brunei each bought one car. The concept of a Lagonda in the brutally corrupt and poverty-stricken environs of Haiti is particularly unattractive. Hopefully it ended up in the South of France where dictators go to spend their ill-gotten gains.

The Lagonda put Aston Martin back on the automotive map and attracted badly needed new attention. The factory eventually got it right, and I hope that current and future owners will find that its value as a classic will begin to reflect the passion and commitment that went into its development.

END

To read the original, unedited piece, visit Peter Sprague's website. You can also visit Peter Sprague's LinkedIn account to learn more and connect.